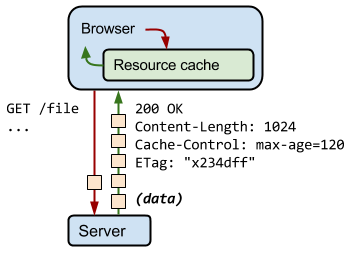

All HTTP requests made by the browser are first routed to the browser cache to check if there is a valid cached response that can be used to fulfill the request. If there is a match, the response is read from the cache and we eliminate both the network latency and the data costs incurred by the transfer.

However, what if we want to update or invalidate a cached response?

For example, let’s say we’ve told our visitors to cache a CSS stylesheet for up to 24 hours (max-age=86400), but our designer has just committed an update that we would like to make available to all users. How do we notify all the visitors with what is now a “stale” cached copy of our CSS to update their caches? It’s a trick question - we can’t, at least not without changing the URL of the resource.

Once the response is cached by the browser, the cached version will be used until it is no longer fresh, as determined by max-age or expires, or until it is evicted from cache for some other reason - e.g. the user clearing their browser cache. As a result, different users might end up using different versions of the file when the page is constructed; users who just fetched the resource will use the new version, while users who cached an earlier (but still valid) copy will use an older version of its response.

So, how do we get the best of both worlds: client-side caching and quick updates?

Simple, we can change the URL of the resource and force the user to download the new response whenever its content changes. Typically, this is done by embedding a fingerprint of the file, or a version number, in its filename - e.g. style.

x234dff

.css.

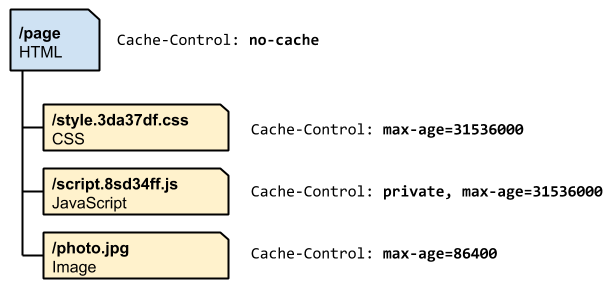

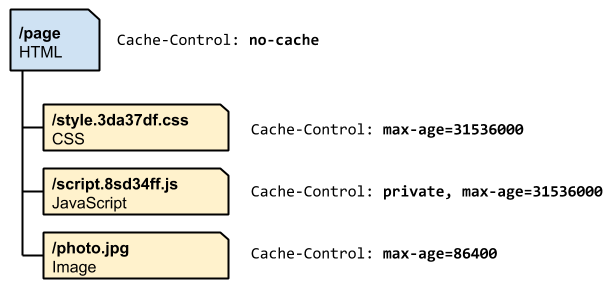

The ability to define per-resource caching policies allows us to define “cache hierarchies” that allow us to control not only how long each is cached for, but also how quickly new versions are seen by visitor. For example, let’s analyze the above example:

-

The HTML is marked with “no-cache”, which means that the browser will always revalidate the document on each request and fetch the latest version if the contents change. Also, within the HTML markup we embed fingerprints in the URLs for CSS and JavaScript assets: if the contents of those files change, than the HTML of the page will change as well and new copy of the HTML response will be downloaded.

-

The CSS is allowed to be cached by browsers and intermediate caches (e.g. a CDN), and is set to expire in 1 year. Note that we can use the “far future expires” of 1 year safely because we embed the file fingerprint its filename: if the CSS is updated, the URL will change as well.

-

The JavaScript is also set to expire in 1 year, but is marked as private, perhaps because it contains some private user data that the CDN shouldn’t cache.

-

The image is cached without a version or unique fingerprint and is set to expire in 1 day.

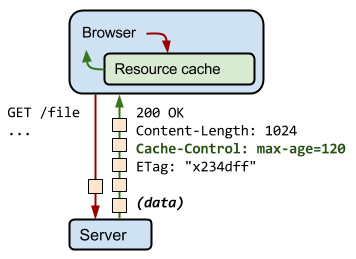

The combination of ETag, Cache-Control, and unique URLs allows us to deliver the best of all worlds: long-lived expiry times, control over where the response can be cached, and on-demand updates.

Caching checklist

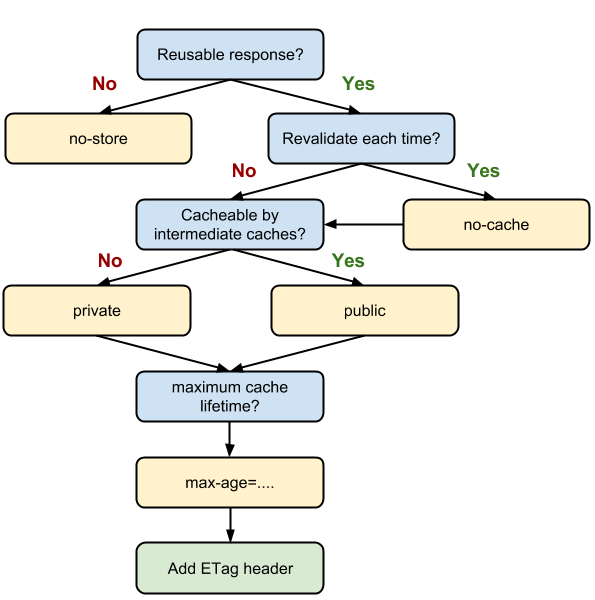

There is no one best cache policy. Depending on your traffic patterns, type of data served, and application-specific requirements for data freshness, you will have to define and configure the appropriate per-resource settings, as well as the overall “caching hierarchy”.

Some tips and techniques to keep in mind as you work on caching strategy:

-

Use consistent URLs:

if you serve the same content on different URLs, then that content will be fetched and stored multiple times. Tip: note that

URLs are case sensitive

!

-

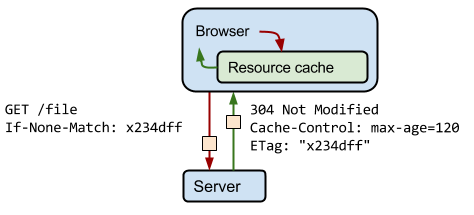

Ensure the server provides a validation token (ETag):

validation tokens eliminate the need to transfer the same bytes when a resource has not changed on the server.

-

Identify which resources can be cached by intermediaries:

those with responses that are identical for all users are great candidates to be cached by a CDN and other intermediaries.

-

Determine the optimal cache lifetime for each resource:

different resources may have different freshness requirements. Audit and determine the appropriate max-age for each one.

-

Determine the best cache hierarchy for your site:

the combination of resource URLs with content fingerprints, and short or no-cache lifetimes for HTML documents allows you to control how quickly updates are picked up by the client.

-

Minimize churn:

some resources are updated more frequently than others. If there is a particular part of resource (e.g. JavaScript function, or set of CSS styles) that are often updated, consider delivering that code as a separate file. Doing so allows the remainder of the content (e.g. library code that does not change very often), to be fetched from cache and minimizes the amount of downloaded content whenever an update is fetched.