In addition to different lossy and lossless compression algorithms, different image formats support different features such as animation and transparency (alpha) channels. As a result, the choice of the “right format” for a particular image is a combination of desired visual results and functional requirements.

|

Format

|

Transparency

|

Animation

|

Browser

|

|

GIF

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

All

|

|

PNG

|

Yes

|

No

|

All

|

|

JPEG

|

No

|

No

|

All

|

|

JPEG XR

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

IE

|

|

WebP

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Chrome, Opera, Android

|

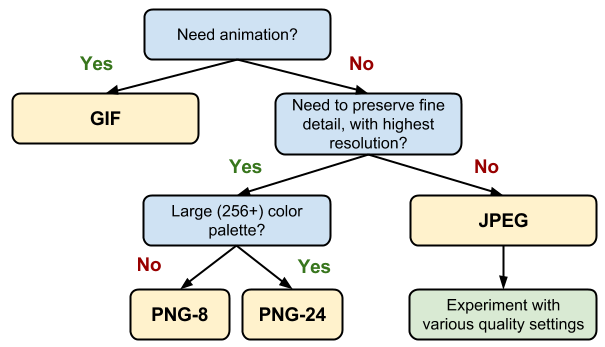

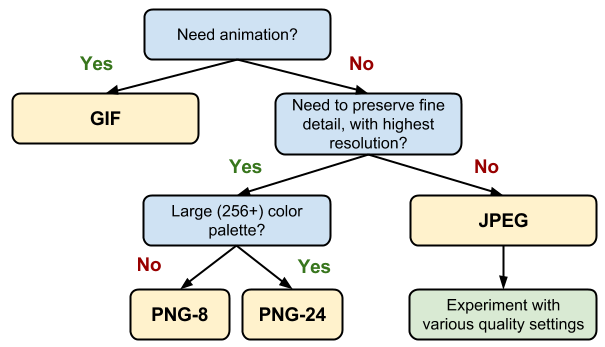

There are three universally supported image formats: GIF, PNG, and JPEG. In addition to these formats, some browsers also support newer formats such as WebP and JPEG XR, which offer better overall compression and more features. So, which format should you use?

-

Do you need animation? If so, GIF is the only universal choice.

-

GIF limits the color palette to at most 256 colors, which makes it a poor choice for most images. Further, PNG-8 delivers better compression for images with a small palette. As a result, GIF is the right answer only when animation is required.

-

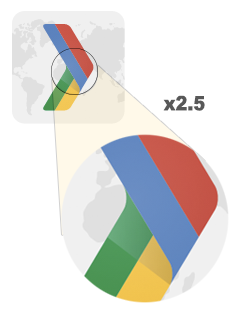

Do you need to preserve fine detail with highest resolution? Use PNG.

-

PNG does not apply any lossy compression algorithms beyond the choice of the size of the color palette. As a result, it will produce the highest quality image, but at a cost of significantly higher filesize than other formats. Use judiciously.

-

If the image asset contains imagery composed of geometric shapes, consider converting it to a vector (SVG) format!

-

If the image asset contains text, stop and reconsider. Text in images is not selectable, searchable, or “zoomable”. If you need to convey a custom look (for branding or other reasons), use a web font instead.

-

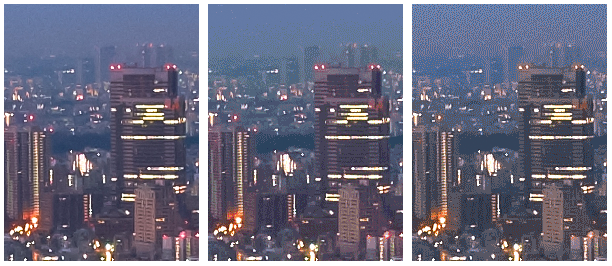

Are you optimizing a photo, screenshot, or a similar image asset? Use JPEG.

-

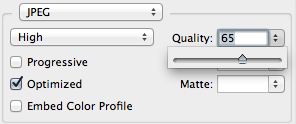

JPEG uses a combination of lossy and lossless optimization to reduce filesize of the image asset. Try several JPEG quality levels to find the best quality vs. filesize tradeoff for your asset.

Finally, once you’ve determined the optimal image format and its settings for each of your assets, consider adding an additional variant encoded in WebP and JPEG XR. Both of of these formats are new, and unfortunately are not (yet) universally supported by all browsers, but they can nonetheless provide significant savings for newer clients - e.g. on average, WebP delivers a

30% filesize decrease

over a comparable JPEG image.

Since neither WebP and JPEG XR are universally supported, you will need to add additional logic to your application or servers to serve the appropriate resource:

-

Some CDNs provide image optimization as a service, including JPEG XR and WebP delivery.

-

Some open-source tools (e.g. PageSpeed for Apache or Nginx) automate the optimization, conversion, and serving of appropriate assets.

-

You can add additional application logic to detect the client, check which formats they support, and serve the best available image format.

Finally, note that if you are using a Webview to render content in your native application, then you have full control of the client and can use WebP exclusively! Facebook, Google+ and many others use WebP to deliver all of their images within their applications - the savings are definitely worth it. To learn more about WebP, checkout the

WebP: Deploying Faster, Smaller, and More Beautiful Images

presentation from Google I/O 2013.

There is no one perfect image format, tool, or a set of optimization parameters that apply to all images. For best results you will have to pick the format and its settings depending on the contents of the image, and its visual and other technical requirements.

Don’t be afraid to experiment with parameters of each compressor. Dial down the quality, see how it looks, then rinse, lather and repeat. Once you’ve found a good set of settings, you can apply them to other similar images on your site, but don’t assume that all images must be compressed with the same settings.

Delivering scaled image assets