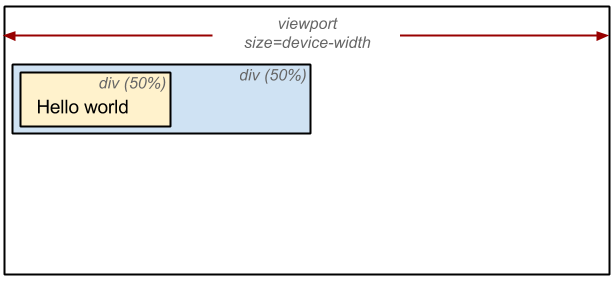

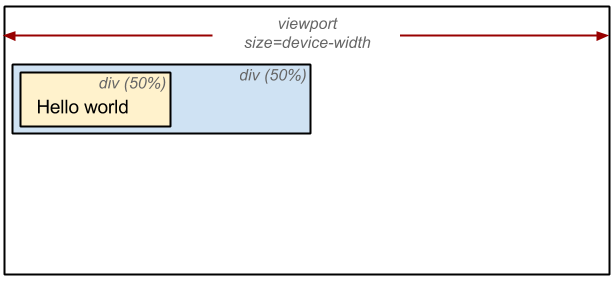

The body of the above page contains two nested div’s: the first (parent) div sets the display size of the node to 50% of the viewport width, and the second div contained by the parent sets its width to be 50% of its parent - i.e. 25% of the viewport width!

The output of the layout process is a “box model” which precisely captures the exact position and size of each element within the viewport: all of the relative measures are converted to absolute pixels positions on the screen, and so on.

Finally, now that we know which nodes are visible, their computed styles, and geometry, we can finally pass this information to our final stage which will convert each node in the render tree to actual pixels on the screen - this step is often referred to as “painting” or “rasterizing.”

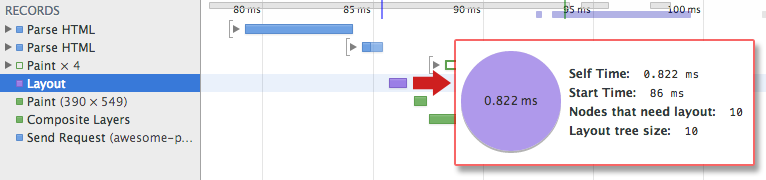

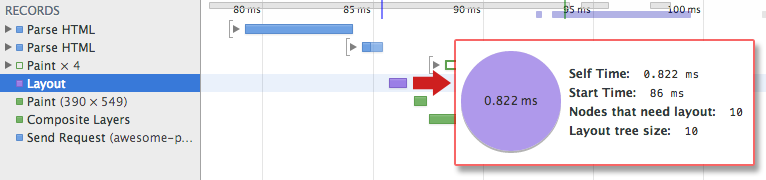

Did you follow all of that? Each of these steps requires a non-trivial amount of work by the browser, which also means that it can often take quite a bit of time. Thankfully, Chrome DevTools can help us get some insight into all three of the stages we’ve described above. Let’s examine the layout stage for our original “hello world” example:

-

The render tree construction and position and size calculation are captured with the “Layout” event in the Timeline.

-

Once layout is complete, the browser issues a “Paint Setup” and “Paint” events which convert the render tree to actual pixels on the screen.

The time required to perform render tree construction, layout and paint will vary based on the size of the document, the applied styles, and of course, the device it is running on: the larger the document the more work the browser will have to do; the more complicated the styles are the more time will be consumed for painting also (e.g. a solid color is “cheap” to paint, and a drop shadow is much more “expensive” to compute and render).

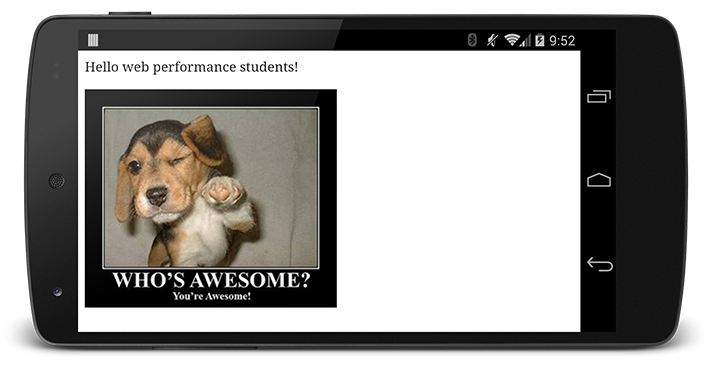

Once all is said and done, our page is finally visible in the viewport - woohoo!

Let’s do a quick recap of all the steps the browser went through:

-

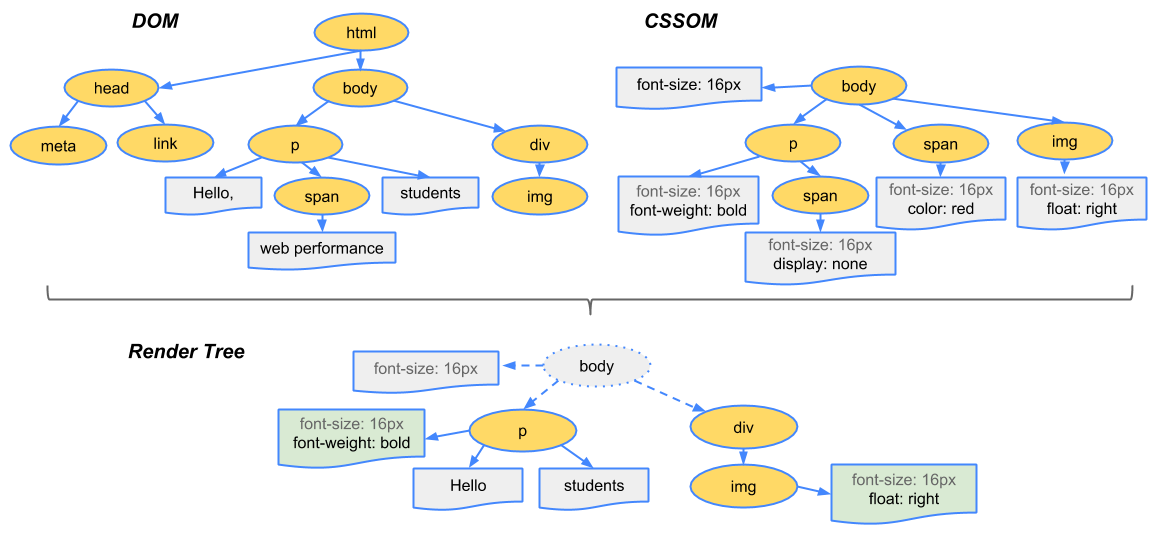

Process HTML markup and build the DOM tree

-

Process CSS markup and build the CSSOM tree

-

Combine the DOM and CSSOM into a render tree

-

Run layout on the render tree to compute geometry of each node

-

Paint the individual nodes to the screen

Our demo page may look very simple, but it requires quite a bit of work! Care to guess what would happen if the DOM, or CSSOM is modified? We would have to repeat the same process over again to figure out which pixels need to be re-rendered on the screen.

Optimizing the critical rendering path is the process of minimizing the total amount of time spent in steps 1 through 5 in the above sequence.

Doing so enables us to render content to the screen as soon as possible and also to reduces the amount of time between screen updates after the initial render - i.e. achieve higher refresh rate for interactive content.