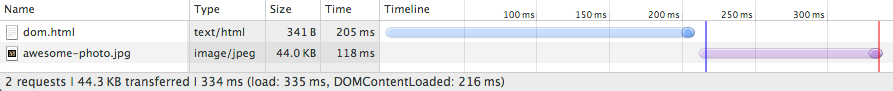

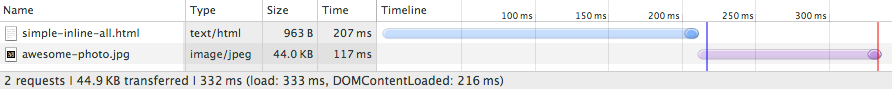

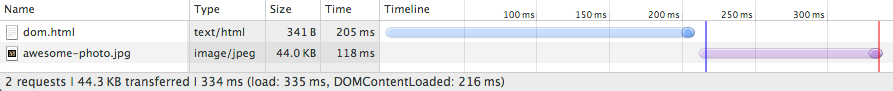

We’ll start with basic HTML markup and a single image - no CSS or JavaScript - which is about as simple as it gets. Now let’s open up our Network timeline in Chrome DevTools and inspect the resulting resource waterfall:

As expected, the HTML file took ~200ms to download. Note that the transparent portion of the blue line indicates the time the browser is waiting on the network - i.e. no response bytes have yet been received - whereas the solid portion shows the time to finish the download after the first response bytes have been received. In our example above, the HTML download is tiny (<4K), so all we need is a single roundtrip to fetch the full file. As a result, the HTML document takes ~200ms to fetch, with half the time spent waiting on the network and other half on the server response.

Once the HTML content becomes available, the browser has to parse the bytes, convert them into tokens, and build the DOM tree. Notice that DevTools conveniently reports the time for DOMContentLoaded event at the bottom (216ms), which also corresponds to the blue vertical line. The gap between the end of the HTML download and the blue vertical line (DOMContentLoaded) is the time it took the browser to build the DOM tree - in this case, just a few milliseconds.

Finally, notice something interesting: our “awesome photo” did not block the domContentLoaded event! Turns out, we can construct the render tree and even paint the page without waiting for each and every asset on the page:

not all resources are critical to deliver the fast first paint

. In fact, as we will see, when we talk about the critical rendering path we are typically talking about the HTML markup, CSS, and JavaScript. Images do not block the initial render of the page - although, of course, we should try to make sure that we get the images painted as soon as possible also!

That said, the “load” event (also commonly known as “onload”), is blocked on the image: DevTools reports the onload event at 335ms. Recall that the onload event marks the point when

all resources

required by the page have been downloaded and processed - this is the point when the loading spinner can stop spinning in the browser and this point is marked by the red vertical line in the waterfall.

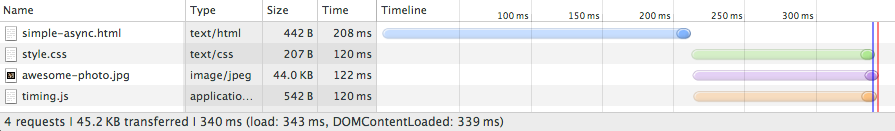

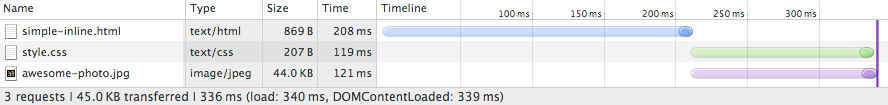

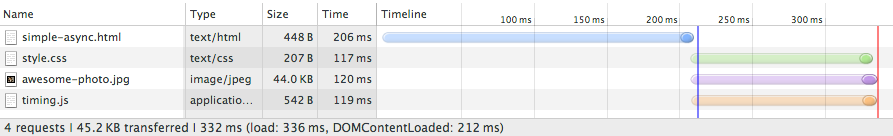

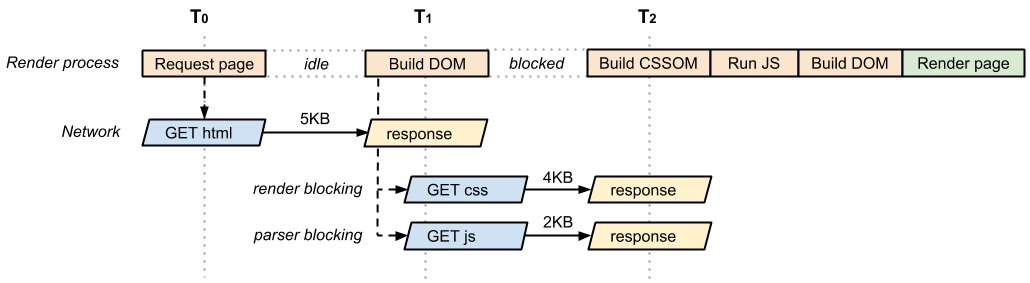

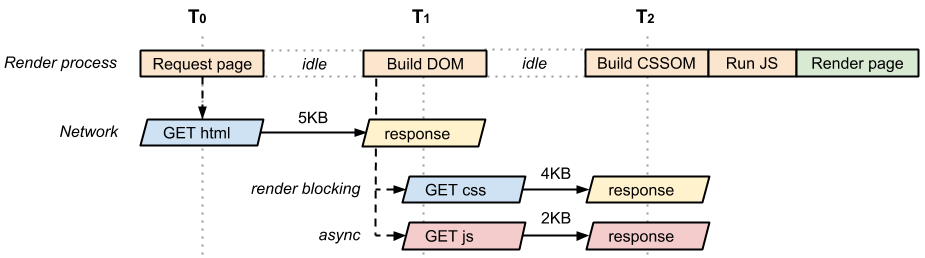

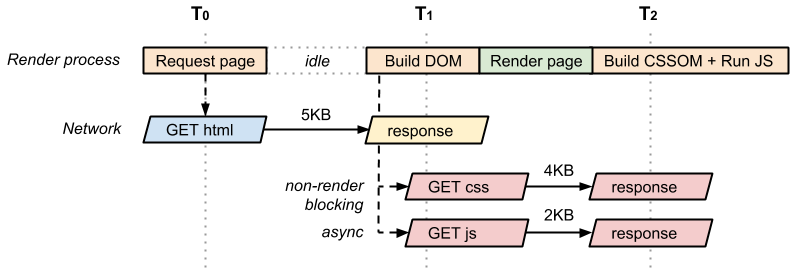

Adding JavaScript and CSS into the mix

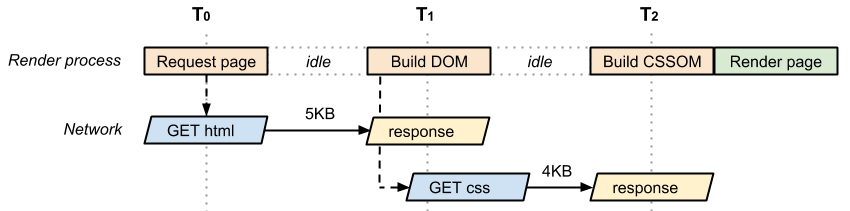

Our “Hello World experience” page may seem simple on the surface, but there is a lot going on under the hood to make it all happen! That said, in practice we’ll also need more than just the HTML: chances are, we’ll have a CSS stylesheet and one or more scripts to add some interactivity to our page. Let’s add both to the mix and see what happens: