-

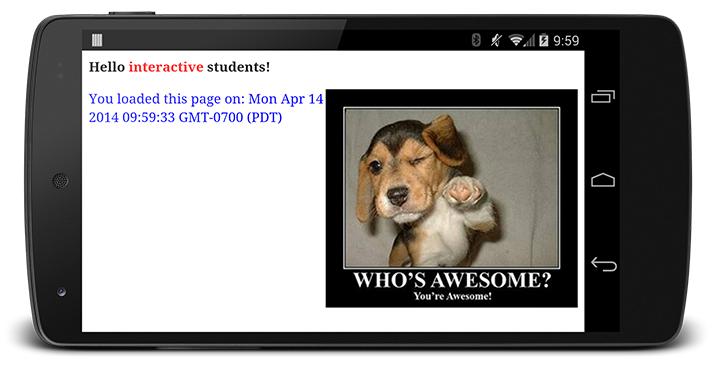

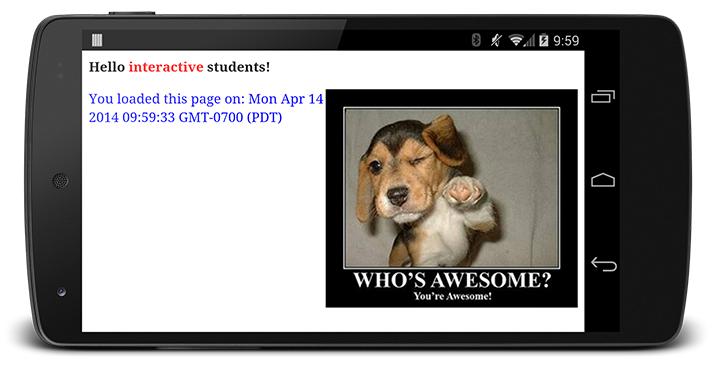

JavaScript allows us to reach into the DOM and pull out the reference to the hidden span node - the node may not be visible in the render tree, but it’s still there in the DOM! Then, once we have the reference, we can change its text (via .textContent), and even override its calculated display style property from ‘none’ to ‘inline’. Once all is said and done, our page will now display “

Hello interactive students!

”.

-

JavaScript also allows us to create, style, and append and remove new elements to the DOM. In fact, technically our entire page could be just one big JavaScript file which creates and styles the elements one by one - that would work, but working with HTML and CSS is much easier in practice. In the second part of our JavaScript function we create a new div element, set its text content, style it, and append it to the body.

With that, we’ve modified the content and the CSS style of an existing DOM node, and added an entirely new node to the document. Our page won’t win any design awards, but it illustrates the power and flexibility that JavaScript affords us.

However, there is a big performance caveat lurking underneath. JavaScript affords us a lot of power, but it also creates a lot of additional limitations on how and when the page is rendered.

First, notice that in the above example our inline script is near the bottom of the page. Why? Well, you should try it yourself, but if we move the script above the

span

element, you’ll notice that the script will fail and complain that it cannot find a reference to any

span

elements in the document - i.e.

getElementsByTagName(‘span’)

will return

null

. This demonstrates an important property: our script is executed at the exact point where it is inserted in the document. When the HTML parser encounters a script tag, it pauses its process of constructing the DOM and yields control over to the JavaScript engine; once the JavaScript engine has finished running, the browser then picks up from where it left off and resumes the DOM construction.

In other words, our script block can’t find any elements later in the page because they haven’t been processed yet! Or, put slightly differently:

executing our inline script blocks DOM construction, which will also delay the initial render.

Another subtle property of introducing scripts into our page is that they can read and modify not just the DOM, but also the CSSOM properties. In fact, that’s exactly what we’re doing in our example when we change the display property of the span element from none to inline. The end result? We now have a race condition.

What if the browser hasn’t finished downloading and building the CSSOM when we want to run our script? The answer is simple and not very good for performance:

the browser will delay script execution until it has finished downloading and constructing the CSSOM, and while we’re waiting, the DOM construction is also blocked!

In short, JavaScript introduces a lot of new dependencies between the DOM, CSSOM, and JavaScript execution and can lead to significant delays in how quickly the browser can process and render our page on the screen:

-

The location of the script in the document is significant

-

DOM construction is paused when a script tag is encountered and until the script has finished executing

-

JavaScript can query and modify the DOM and CSSOM

-

JavaScript execution is delayed until the CSSOM is ready

When we talk about “optimizing the critical rendering path,” to a large degree we’re talking about understanding and optimizing the dependency graph between HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

Parser Blocking vs. Asynchronous JavaScript

By default, JavaScript execution is “parser blocking”: when the browser encounters a script in the document it must pause DOM construction, hand over the control to the JavaScript runtime and let the script execute before proceeding with DOM construction. We already saw this in action with an inline script in our earlier example. In fact, inline scripts are always parser blocking unless you take special care and write additional code to defer their execution.

What about scripts included via a script tag? Let’s take our previous example and extract our code into a separate file: